It’s something that has probably happened to you dozens of times, whether you’re at your annual physical, you’re at immediate care for a nasty cough, or you’ve taken a trip to the emergency room: Your provider has listened to your heart with their stethoscope.

You know they’re listening to your heartbeat, but what exactly are they listening for when they press their stethoscope against your chest?

They’re looking for that familiar “lub-dub” — the sound of your heart valves opening and closing as blood flows through the heart. But sometimes, that rhythmic “lub-dub” is interrupted by an abnormal swishing, whooshing, or blowing noise in between heartbeats. This extra noise is called a heart murmur. Heart murmurs are actually very common.

Here are 5 things to know if you or your child have been told that you have a heart murmur.

1. Many murmurs are completely innocent.

In general, there are two types of heart murmurs: innocent and abnormal.

Innocent murmurs are harmless sounds made as blood flows normally through a healthy heart or blood vessels close to the heart. Many infants and children have these types of murmurs, since their hearts are close to their chest walls and it’s easy to hear the blood flow. The murmurs often disappear during adulthood, but they can sometimes stick with someone throughout their life.

These murmurs can pop up when blood flows quicker through the heart than usual. Exercise and physical activity, pregnancy, and rapid growth spurts can all bring on an innocent murmur.

If you find out that you or your child have an innocent murmur, rest easy. Innocent murmurs do not cause any symptoms and are not a type of heart disease. They don’t require any treatment and should not stand in the way of living a normal life. Plus, they are totally normal — up to 72% of children and adolescents may have a murmur at some point.

2. You still need to take heart murmurs seriously.

Abnormal murmurs are caused by other problems in the heart. Some of the most common include:

- Valve problems can occur in any of the four heart valves. The valves are responsible for letting blood flow from the heart’s upper chambers to the lower chambers. Several types of valve problems can cause heart murmurs, such as:

- Stenosis (a narrowed valve that doesn’t open correctly)

- Regurgitation (a leaky valve)

- A hole in the septum, which is the wall dividing the left and right upper or lower chambers of the heart

- Patent ductus arteriosus (the ductus arteriosus blood vessel doesn’t close after birth) – causing abnormal flow between chambers of the heart.

- Endocarditis is an infection and swelling of the lining of the heart (endocardium) and the valves that can obstruct blood flow or cause blood to leak backwards.

- Cardiomegaly is an enlarged heart. If the heart is too large, it can have difficulty pumping blood efficiently.

While murmurs themselves aren’t symptomatic, the underlying causes can lead to symptoms like dizziness, shortness of breath, or chronic cough.

Do you have questions about your heart murmur? Schedule an appointment with a Duly Health and Care cardiologist.

3. There are several ways to determine the type of heart murmur — and what’s causing it.

You can’t hear a heart murmur without listening to your heart through a stethoscope. That’s why most murmurs are found during routine exams, when your provider is checking your heartbeat.

So — how does your provider know if it’s innocent or abnormal?

When they first hear the murmur, they can classify it on a scale from 1 to 6, with 6 being the loudest and most intense. Murmurs that are graded higher on the scale may be a bit more worrisome.

They will also evaluate the timing of the murmur, and when it occurs in the heartbeat. A systolic murmur, which happens as blood is leaving the heart, is often innocent. However, a murmur that occurs when the heart is filling up with blood (diastolic) or that goes through the entire heartbeat (continuous), is more suspect.

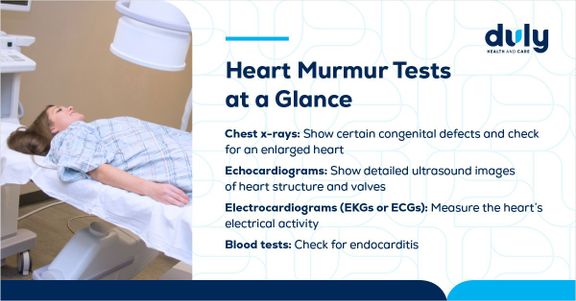

If your provider does suspect that it’s more than an innocent murmur, they may recommend some additional tests, like x‑rays or electrocardiograms.

4. Murmurs themselves don’t require treatment.

You don’t need treatment for a murmur — but you may need treatment for what is causing it. Many of the diseases and conditions that cause murmurs can be treated with medication. In certain cases, where the disease is severe, you may need surgery.

If you know that you or your child have a heart murmur — even an innocent one — always be on the lookout for signs of a more serious condition, like constantly being very tired or having difficulty exercising and being physically active. Call your provider or your child’s provider right away if you notice:

- Chest pain

- Difficulty feeding

- Fast breathing

- Shortness of breath

- Bluish tint to the lips or skin

- Swelling in the legs

5. You don’t need to panic.

Remember — a heart murmur itself isn’t a form of heart disease. Even if you have an abnormal murmur, the condition causing it is often treatable. Most murmurs are not serious and won’t stand in the way of living a normal, healthy life.

Health Topics: